Fare evasion is a global issue causing losses of billions of euros.

Washington D.C. ranks third in the US for the financial impact caused by fare evasion, after Massachusetts’ Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) and New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA).

In 2019, fare evasion losses on buses amounted to €24.4m ($29m), and €9.2m ($11m) on the subway, bringing the tally to a total of €33.6m ($40m).

By contrast, fare evasion losses at MBTA amounted to €35.4m ($42m), and €181m ($215m) at MTA in 2019.

According to WMATA, acts of fare evasion include any incidents when adults or students do not tap their cards for any reason, as well as instances when riders can not pay because of broken fareboxes or malfunctioning card validation machines.

Compared to 2018, ridership increased on the subway by 4% to 182 million trips in 2019, and decreased on busses by 3.5% to 289.000 trips.

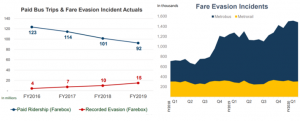

Fare evasion rates have increased over the past years, most notably on busses as shown in the graphs below released by WMATA:

WMATA reports passenger and fare evasion numbers differently on buses and on the subway.

On busses it uses Fare Box Keypads and Automatic Passenger Counter electronic systems to keep count of riders and fare evasion. These are not always accurate and are prone to both human and computer errors.

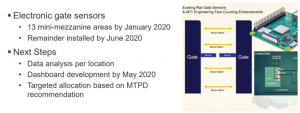

On the subway it did not have a system in place to count passengers or fare evasion rates until last year.

In the past year the agency started testing new systems to count ridership using sensors installed at the fare gates, and video analytics from surveillance cameras.

According to the agency, the data from these systems will be used to compare the difference between passengers counted and collected revenue to better estimate fare evasion rates, to discourage crime, and to provide data for organising deployment strategies by the Metro Police force.

Offence rates linked to counting errors and young Black riders

So who are people not paying on Washington’s public transport?

A large portion of the unaccounted ridership and fare evasion in the past few years might come from students who qualified for free trips through the Kids Ride Free program but did not tap their cards, as reported by a WTOP investigation from November 2018.

A public oversight roundtable in November 2019 confirmed that amid multiple changes made to the card system by the WMATA, the students were not able to tap their cards or were told that it was not necessary to do so, leading to an increase in reported fare infractions.

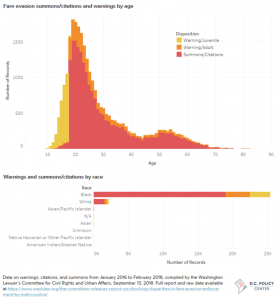

A 2018 report issued by the Washington’s Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights and Human Affairs found that 91% of all citations and summons for fare evasion were issued to Black riders, and 46% of these were issued to Black young adults and youth under the age of 25.

In the report, WMATA states that around 10.000 persons were stopped for fare evasion in 2018. It does not mention how many people received warnings or summons, or were arrested, but the Metro Transit Police Department stated that about 8% of the stops led to arrests.

Fare evasion – a global issue

Fare evasion is a major concern for mass transport companies, even more now as they are working to recover financial losses during the pandemic.

While passenger numbers plummeted, fare infraction rates skyrocketed in the first months of the Covid-19 outbreak, as ticket inspections and front-door bus boarding were halted.

Breakthrough technologies using AI Video Analytics provide an alternative solution to tackle fare evasion at turnstile gates, by detecting infractions through video streams in real-time. This technology allows for faster response times, and selective controls which are better suited in the context of the pandemic.